|

5 - Lyngbye's

interpretation

Again, Candolle was not explicit in the Flore about the origin or meaning of the name. But the literature on diatoms over the next two decades (1805-c. 1825) overwhelmingly shows the recurrent focus of description is the zig-zag nature of a diatom's or Diatoma's filament, not the substructure within the segments composing the filaments. There is no description in this literature commensurate with the idea of bipartiteness of the segments. Although some very few illustrations show transverse or longitudinal lines drawn within a segment, potentially indicating septa, intercalary bands or valve-mantle junctions, or even recently divided cells, any such interpretation of them as such comes from us, because it was absent from the authors' characterizations. From the perspective of our query one work in this literature is striking. Diatoms began to coalesce as a homogeneous group in the hands of the Danish botanist, Hans Christian Lyngbye, in his first, only, but classic work in 1819 -- An Attempt at a Study of the Aquatic Plants of Denmark [Tentamen Hydrophytologiae Danicae]. At this time Denmark ranged from Holstein at the base of the Jutland peninusula to its tip, across the archipelago of Baltic islands to the Faeroe Islands and Greenland, so Lyngbye's collections, largely marine, were extensive. He segregated 49 genera of "hydrophytes" into six groups, one of which was composed of 14 species, and which we would today accept as diatoms, except for one species. He split this group into two genera: Candolle's Diatoma and a new genus of his own, Fragilaria (See Marginalia no. 2). Diatoma contained species we would find today in Diatoma, Tabellaria, Grammatophora, Rhabdonema, Isthmia and Biddulphia, and Fragilaria was similarly compounded. But more important than these historic medleys was his diagnosis of the two genera, as revealed in these portions of their descriptions:

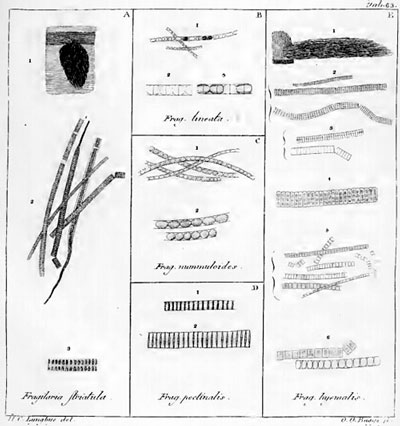

Figure 13. The contrast

between the zig-zag filaments of Diatoma (left) and the "linear"

filaments of Fragilaria (right) is well illustrated in these

two plates from Lyngbye (1819). Plate 61 illustrates 6 Diatoma

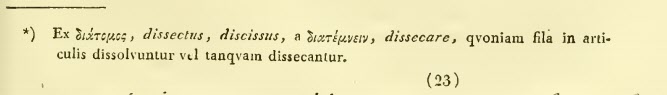

species; Plate 63 illustrates 5 Fragilaria species. The filaments of both genera broke apart [solutis] into segments [articulis], but in Diatoma those segments continued to cohere alternately at their angles [angulo.alternatim cohaerentibus]; they did not do so in Fragilaria. The novelty was not the splitting apart but the protracted coherence following the division, but it is clearly the filaments which broke apart, not the articles. Zig-zag filaments characterized Diatoma, not Fragilaria. But even more importantly, in a footnote to the genus Diatoma Lyngbye provided the first explicit interpretation of the name's etymology:

Figure 14 (left). From H. C. Lyngbye's

Tentamen Hydrophytologiae Danicae (1819). ...

The filaments were cleaved into articles, not the articles cleaved into pieces. Thus, Candolle appears to have taken Linnaeus to heart in choosing the name. In Philosophia botanica (1751) Linneaus advised botanists that "Generic names that show the essential characters or habit [external appearance] of the plant are best" (Aphorism 240) and "The habit indicates a likeness for which an image is produced and from the image a name" (Aphorism 163). One of Linnaeus' primary aims was identification, and treating humans as primarily visual animals, he wanted generic names to gel in one's mind's eye. Cleft conferva, indeed! |

| <-- 4 - Path to Diatoma in Candolle's key |

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

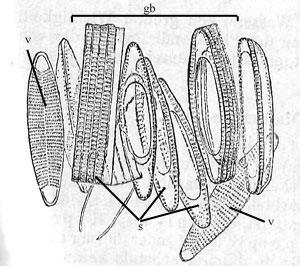

Figure

12 (left). The wall of one cell of Rhabdonema arcuatum from an

original drawing by William Smith (1856) reproduced by Karsten in Engler

& Prantl's Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien (1928) showing

the separation of the cell wall into two valves (v) and multiple intercalary

girdle bands (gb) with septa (s). Annotations are not part of the original

drawing.

Figure

12 (left). The wall of one cell of Rhabdonema arcuatum from an

original drawing by William Smith (1856) reproduced by Karsten in Engler

& Prantl's Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien (1928) showing

the separation of the cell wall into two valves (v) and multiple intercalary

girdle bands (gb) with septa (s). Annotations are not part of the original

drawing. ..................

..................